World Passwordless Day?

Can you easily recall your email account password? Is your password, by any chance, something memorable to you, like the name of a pet, or a colour? Is it a word? If the answer to any of these questions is yes, then it’s likely that your password is not strong enough.

Let’s say I bought my first pet in London, in 2020. As this is quite easy for me to remember, I make my password:

london2020

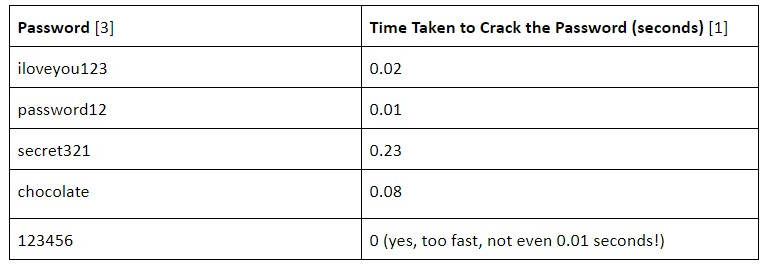

It’s easy to remember and I will never have to go through the hassle of forgetting my password…Except that this password could only take just 11.88 seconds to crack and I could now have easily become the victim of a password attack [1]. To add to that - a shocking 64% of people may be reusing their passwords, giving attackers further opportunities to exploit [2]! “london2020” is not the only password that could be cracked this fast. Do any of the below passwords ring a bell?

Table 1: Time taken for five passwords to be cracked.

So yes, this is no time to use passwords anymore; passphrases are what we need. If the numbers above still do not convince you, make sure you read on.

Today is the 9th World Password Day, an annual event started by Intel Security to spread awareness about the importance of keeping your online accounts safe. In this article, we aim to explore the history of passwords, threats associated with the use of passwords, how you can improve yours, and the potential of passwordless authentication.

A Brief History of Passwords

Let’s start with a brief history of where passwords came from:

1961 - The earliest documented use of a password. One of the earliest documented uses of a password was on MIT's Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS) led by Fernando Corbató, where multiple users needed to access their own private set of files [4].

1962 - The earliest documented case of password theft. Alan Scherr, a PhD student, stole the passwords of the CTSS system when he needed more than the allocated time of 4 hours per semester to run his simulations. This ‘hack’ didn’t require much coding though - Scherr simply requested a printout of the system’s password file and received it early the next morning [4]!

1966 – One of the first hashing functions was implemented. The Cambridge Multiple Access System (CMAS) used a one-way function to protect its password file, meaning that even if the password file was accessed, it was still quite hard to extract the passwords themselves [5].

1973 – Hashing was implemented in UNIX Version 3. A one-way function was implemented into one of the fundamental operating systems, UNIX. Robert Morris adapted an encryption program based on the M-209 cipher machine to protect the system’s password file [6].

1979 – The term ‘salting’ was coined and implemented in UNIX Version 7. Robert Morris and Ken Thompson added a system that added a random 12-bit number to each password. This meant that it was much harder to ‘crack’ passwords (extract them from their hashed equivalent through brute force) and make it nearly impossible to tell if a password was used twice by multiple people or multiple systems [6].

1995 – The first two-factor authentication patent was filed. AT&T filed a US patent for a system that used a two-way pager to authorise transactions in addition to a customer identifier (e.g. PIN or password) [7].

1999 – One of the first password managers, RoboForm, was released. Siber Systems released their first consumer product RoboForm, which allowed users to generate and store random passwords for each of their accounts [8].

2009 - RockYou password breach. The social media site RockYou suffered a major data breach that exposed over 32 million user accounts and their plain text passwords. The list of these passwords has since become well-known within cybersecurity, being included in many cybersecurity operating systems by default [9].

2011 - RFC 6238 was published for Time-Based One-Time Passwords (TOTP). A Request for Comments (proposed internet standard) was published that described an algorithm for generating random ‘two-factor authentication’ codes based on the current time. This is what is commonly used today [10].

2013 - First World Password Day. Intel Security began World Password Day, which has fallen on the first Thursday in May every year since.

How Can My Password Get Stolen?

Physical Access

Imagine you forget your laptop in a cafe for a few minutes before you remember and come back to the cafe to get it. During those few minutes, an attacker could conduct a cold boot attack to dump the RAM of the computer, which could very well give them access to passwords and other sensitive information once analysed using a tool like Volatility [11].

In most cases, the passwords will be hashed. But, those hashed passwords can be cracked. There are a few tools (e.g. hashcat, John) that can do this for both Windows and Linux hashes and therefore passwords compromised through physical access and thereafter analysis can lead to a myriad of problems.

Remote Access: Phishing

There also are relatively reliable methods through which your password could become compromised entirely remotely. You are likely to have heard of phishing, a means through which an unethical actor may illegally compromise personal information from a user. Oftentimes, this is through email, and the user is socially engineered to enter their credentials in some way or form to access a service that the sender of the email is claiming to offer.

Figure 1 - Uncontextualised phishing email example. By clicking on the link, the user would enter their credentials and the attacker can harvest these. Since, as mentioned above, a lot of users reuse their passwords, the attacker can try the credentials on other sites and potentially gain illegal access to the user’s account, leading to a lot of further problems. Figure created by Author.

Fig. 1 shows an example of a basic form of a phishing email. You have probably already noticed that there are many grammatical and spelling errors in the message. Some other defining features of this phishing email include:

Not specifying the recipient (“dear Sir”)

The sense of urgency in the message - the sender is actively encouraging the user to click on the link.

Although a secure session may still get compromised or used in a phishing attack, the use of a “http” link that is not secure is a big red flag.

However, 1 in 4 employees still get phished, and phishing methods can get a lot more convincing and sophisticated - and one of the ways through which this level of advancement is achieved is by using contextual information [12]. Contextual information can be obtained from many sources such as social media profiles, job profiles, and special tools such as Spiderfoot which can be used to collect information around a victim to be able to target them more easily.

Let’s say, Alison, an avid football fan, who is very active on Twitter has bought a very high-value, customised football kit.

Figure 2 - A Tweet by Alison announcing that she has bought Wom United’s current season’s football kit. Alison and the football team Wom United are both fictional. Figure created by Author.

An attacker can easily leverage a lot of information through this Tweet:

Alison supports Wom United

Alison has paid a lot for the football kit and is likely to be at least a bit anxious about this

Alison owns - or at least has used - an iPhone

An attacker could exploit this through crafting a very contextualised phishing email - increasing the chances of having Alison give up her credentials.

Figure 3 - A contextualised phishing email that aims to gain the trust of the user through contextual information. Figure created by Author.

The convincing nature of the email in Fig. 3 means that the recipient may be more likely to click this link than the one included in Fig. 1. Upon clicking on such a link, the user may be prompted to enter the credentials to log in. However, the attacker is likely staging a compromised version of the site to harvest Alison’s credentials. These credentials can then be used by the attacker on Alison’s other accounts in case she has reused passwords. Further, the attacker could also insert a malware payload that would be automatically installed on Alison’s computer. This malware could be a keylogger, which automatically records the keystrokes of Alison when she is typing on her computer and could result in the attacker gaining insight into her other passwords and potentially other sensitive information. This is just one of many examples of the type of malware that could be integrated here.

These are some ways that password attacks can occur, and to protect against these, you need to be incredibly cautious with clicking on links and generally not open unexpected emails, as well as maintaining a high degree of operational security to not allow for physical access attacks to occur.

But I’ve got nothing to hide…So what’s the risk?

Passwords are used as a means of authentication - to prove that it’s actually you behind the computer screen. This is why you should never share them with another person.

If somebody logged into your Twitter account and made a discriminatory tweet, you would receive the full blame

If somebody accessed inappropriate content on your account, all actions they did would be recorded as you - which could, in some cases, result in a police visit

If you use the same password for multiple accounts, they could reuse your credentials for other websites that you did not intend for them to access

Even if you do not use the same password, if you granted them access to your email address (for example), they could then use this to pivot to other accounts

Even if you fully trust the other person, you do not know how they are storing your password - they may write it down on paper or store it in a publicly shared browser

How Can I Create a Good Password?

In an ideal world, a secure password would be a randomly generated string over 20 characters long that includes letters (upper and lowercase), numbers and symbols. And this password would just be used for one account!

Realistically, however, if you are not using a password manager (more information below), usability needs to be taken into account. There is no definite rule, but these are several pointers that may help:

Do not use common passwords, e.g. password123

Do not include your personal information or information that could be found on your social media accounts. This includes names, favourite places and significant dates

Do use a combination of lowercase letters, uppercase letters, numbers and symbols. This will mean that a brute force attack will take much longer (there are only 26 lowercase characters, but there are over 80 possible characters)

Do use a minimum length of 12-15 characters

You could use three random, unrelated words such as ‘laptopBicycleCan57!’. This is recommended by the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre [13]

You could use a rule on a memorable sentence, such as using the first two characters of each word in ‘Youth STEM 2030 recommends that you use a safe password’ (YoST20rethyousasapa)

How Should I Protect My Passwords?

Do use different passwords for different accounts

Do use multiple, different passwords, even if it isn’t one per account. More is better, but you could start with having a different password for high-risk accounts (e.g. banks and emails) and low-risk accounts (e.g. social media).

Do not change passwords too often

While some cybersecurity experts recommend changing passwords once every 30 to 90 days, this does not make accounts more secure [14]. When related policies are enforced, people are then required to memorise more passwords, resulting in the creation of weaker ones. They would also be keener on making slight variations of previous passwords or reuse older ones. It is best to create secure, long, unique, and easy-to-remember passwords to use in the longer run.

Do use two-factor authentication

Two-factor authentication is a security process, requesting users to provide two distinct factors before being granted access to accounts or systems [15]. The most common factors include [16]:

- Knowledge factors (e.g. passwords, PINs)

- Possession factors (e.g. smartphones, mobile devices, security tokens to approve authentication requests)

- Biometric factors (e.g. fingerprint, facial, voice recognition)

Various organisations including Google and Facebook have already implemented two-factor authentication, so to keep your accounts secure, you can use this authentication for your accounts starting today [17, 18].

Do use a dedicated password manager

With so many different, strong and unique passwords for different accounts, how could we possibly remember them all? A password manager is a vault for you to securely store all your passwords. There are multiple benefits in using one, including storing passwords in encrypted forms and generating secure and random passwords for your accounts [19]. To enter the manager, all you have to memorise is one master password, and the manager will automatically fill in the corresponding password for your accounts.

While there are in-browser password managers, third-party dedicated password managers have an advantage by being cross-platform and cross-browser.

Do use biometrics

If biometric recognition (e.g. fingerprint or facial recognition) are provided as login methods, do use them! Smartphones and the accounts of organisations that require a higher level of security (e.g. financial institutions) tend to provide this option, and you do not have to remember one more password as you are the only one with such biometrics [20].

Here’s answers to are some further questions you might have…

Are password managers safe?

Good password manager companies, such as 1Password and LastPass, protect your passwords with strong encryption (AES-256) [21]. Password managers provide different options for you to access your vault, by using a master password, two-factor authentication, and biometric authentication for an extra layer of security. They have also undergone third-party audits and code reviews to eliminate risks, and have not suffered any security breaches. To learn more, you can check out their websites for more details [22, 23].

If you would like to store them yourself, open-source password managers (e.g. Bitwarden, Keepass) give you the option to store passwords on your own devices or servers, but they typically require more manual and complex work [24, 25].

How often should I change my password?

It is best if you come up with new, unique, and secure passwords every 30 to 90 days to change them with your current ones. However, if you only change passwords to those with similar variations or previously used ones, creating a stronger and secure password at the very beginning is much better than changing it with weaker passwords.

But of course, if your accounts are involved in passwords or data breaches, you would have to change your password immediately. There are multiple websites for you to check whether your personal data had been compromised by any data breach. For instance, you can check out the website “Have I Been Pwned?”, which only requires you to enter your email address [26].

Passwords are such a hassle – can we get rid of them soon?

You are in luck – passwordless authentication is actually on the rise! With so many vulnerabilities when it comes to using passwords, passwordless authentication provides us with better security by eliminating attack vectors and poor password management practices. More and more platforms are incorporating passwordless authentication, with the uses of:

- Proximity cards

- Physical tokens

- Single-use codes or links

- Software tokens or certificates

- Biometric recognition (e.g. fingerprint, voice, facial recognition, retina scanning)

- Smartphone apps

Standards are also being set for browsers and platforms to implement stronger and more secure authentication methods. An official web standard has been set by The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and the FIDO Alliance, known as The Web Authentication (WebAuthn) specification. Provided with testing tools and certification programmes, WebAuthn specification is for web services and apps to provide secure and easier online experiences for all users to use passwordless authentication, which one more step towards reducing reliance on passwords and enforcing stronger authentication methods [27].

What's in Store for the Future?

Passwords are the gatekeepers to our digital identities, and World Password Day is here to remind us all of better password habits. However, with the increasing vulnerabilities that the usage of passwords brings, perhaps we should take this day to review and implement the more secure authentication options, and hopefully, sometime in the future, we will be celebrating World Passwordless Day instead.

References

[1] My1Login, “Password Strength Meter,” n.d. [Online]. Available: https://www.my1login.com/resources/password-strength-test. [Accessed 6 May 2021].

[2] Google / Harris Poll, "Online Security Survey," February 2019. [Online]. Available: https://services.google.com/fh/files/blogs/google_security_infographic.pdf. [Accessed 6 May 2021].

[3] W. J. Burns, "Common Password List ( rockyou.txt )," January 13, 2019. Distributed by Kaggle. [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/wjburns/common-password-list-rockyoutxt. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[4] IEEE Computer Society, "The Compatible Time-Sharing System (1961-1973) Fiftieth Anniversary Commemorative Overview," 2011. Available: https://www.multicians.org/thvv/compatible-time-sharing-system.pdf. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[5] H. Bidgoll, The Internet Encyclopedia, vol. Three, pp. 44, John Wiley & Sons, 2004. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=wshm3f0hyI8C&pg=PA4&lpg=PA4. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[6] R. Morris and K. Thompson, "Password Security: A Case Study," Communications of the ACM, vol. 22, no. 11, pp. 594-97, 1979. Available: https://doi.org/10.1145/359168.359172.

[7] G. E. Blonder, S. L. Greenspan, J. R. Mirvelle and B. Sugla, "Transaction authorization and alert system," U.S. Patent 5 708 422, January 13, 1998.

[8] Goodsync, "About Us," n.d. [Online]. Available: https://www.goodsync.com/about-us. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[9] N. Cubrilovic, "RockYou Hack: From Bad To Worse," TechCrunch, December 15, 2009. [Online]. Available: https://techcrunch.com/2009/12/14/rockyou-hack-security-myspace-facebook-passwords. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[10] D. M'Raihi, S. Machani, M. Pei, and J. Rydell, “TOTP: Time-Based One-Time Password Algorithm,” Internet Engineering Task Force, May 2011. [Online]. Available: https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc6238. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[11] J. Halderman et al., "Lest we remember," Communications of the ACM, vol. 52, no. 5, pp. 91-98, 2009. Available: https://doi.org/10.1145/1506409.1506429.

[12] KnowBe4, "2018 Phishing By Industry Benchmarking Report," 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.knowbe4.com/hubfs/KnowBe4-Phishing-By-Industry-Benchmarking-Report-Partners.pdf. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[13] National Cyber Security Centre, "Top tips for staying secure online," December 17, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/collection/top-tips-for-staying-secure-online/use-a-strong-and-separate-password-for-email. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[14] D. Johnson, "How often you should change your passwords, according to cybersecurity experts," Business Insider, June 26, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.businessinsider.in/tech/how-to/how-often-you-should-change-your-passwords-according-to-cybersecurity-experts/articleshow/76635311.cms. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[15] J. Fruhlinger, "2fa explained: How to enable it and how it works," CSO, September 10, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.csoonline.com/article/3239144/2fa-explained-how-to-enable-it-and-how-it-works.html. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[16] L. Rosencrance, P. Loshin, and M. Cobb, "What is Two-Factor Authentication (2FA) and How Does It Work?," Tech Target, January 2020. [Online]. Available: https://searchsecurity.techtarget.com/definition/two-factor-authentication#:~:text=The%20user%20has%20provided%20two,YubiKey%20is%20the%20possession%20factor. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[17] Google, "Google 2-Step Verification," n.d. [Online]. Available: https://www.google.com/landing/2step/. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[18] Facebook, "What is two-factor authentication and how does it work on Facebook?," n.d. [Online]. Available: https://www.facebook.com/help/148233965247823. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[19] emhiso, "Benefits of Using a Password Manager," Rochester Institute of Technology, December 12, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.rit.edu/security/content/benefits-using-password-manager. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[20] E. Grant, "The rise of biometric technology in banking," Finance Digest, n.d. [Online]. Available: https://www.financedigest.com/the-rise-of-biometric-technology-in-banking.html. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[21] M. Cobb, "What is AES Encryption and How Does it Work?," Tech Target, April 2020. [Online]. Available: https://searchsecurity.techtarget.com/definition/Advanced-Encryption-Standard. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[22] 1Password, "About the 1Password security model," December 15, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://support.1password.com/1password-security/. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[23] LastPass, "LastPass Security History," n.d. [Online]. Available: https://www.lastpass.com/security/what-if-lastpass-gets-hacked. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[24] Bitwarden, "How Bitwarden Works," n.d. [Online]. Available: https://bitwarden.com/products/#how-bitwarden-works. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[25] D. Reichl, "KeePass Password Safe," KeePass, n.d. [Online]. Available: https://keepass.info/. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[26] Technological University Dublin, "Have I been Pwned?,” n.d. [Online]. Available: https://www.dit.ie/aadlt/ictservices/security/protectyourid/haveibeenpwned/. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

[27] SecurityBrief New Zealand Newsdesk, "W3C and FIDO Alliance finalise web standard for passwordless logins," March 5, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://securitybrief.co.nz/story/w3c-and-fido-alliance-finalise-web-standard-for-passwordless-login. [Accessed 6 May 2021]

Publisher’s Note

This article is intended to raise awareness about passwords and any unethical use of this content is not intended. Make sure to abide by your country’s laws.